Vassa and Sierra Leone

Gustavus Vassa had interesting connections with Sierra Leone. When he campaigned to end the slave trade, he could not know that the British Government would use Freetown as the base of their naval and legal campaign to abolish the Atlantic slave trade after 1807, ten years after his death and the end of his personal involvement in the abolition movement. He had wanted to return to Africa and tried to do so, under the misguided mentorship of the disgraced former Governor of the short-lived Province of Senegambia, the first British attempt to establish a formal colony in Africa that was modeled on its colonies in the Americas. Vassa came to work for Governor Mathias McNamara in London as his hair dresser, moving into McNamara's house at a time when the Governor had been unceremoniously dismissed, accused of abuse of office, and convicted in British courts, although retaining considerable wealth that he had illegally acquired while serving in first Fort St.James on the Gambia and then at St. Louis on the Senegal River. McNamara even sponsored Vassa in the attempt to gain a missionary appointment to Africa with the Anglican Bishop of London, which was denied. The reasons have not been uncovered, but it is likely that McNamara's bad reputation didn't help, and Britain was in the midst of its losing battle to prevent 13 colonies in North America from gaining their independence, There was also the fact that the Anglican Church already sponsored one outpost on the Gold Coast that was far from successful.

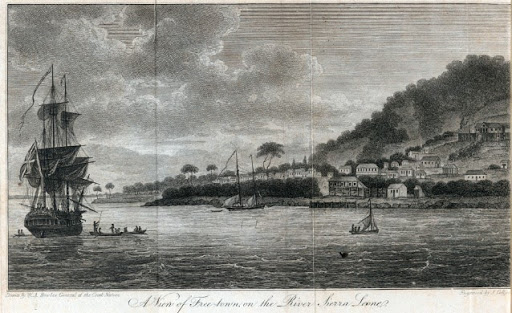

Vassa later became involved in the first attempt to settle a colony on the peninsula at the mouth of the Sierra Leone River, being appointed Commissioner of the Black Poor in late 1786, the official in charge of the well being of the poor Blacks of London and destitute white women who were living off prostitution. Vassa's involvement in this scheme was relatively short lived. He became convinced that the migration was being poorly managed and even that funds were being embezzled and as a result would prove a failure. When he objected all too publically, he was removed from his position, although his warnings unfortunately proved to be accurate. Many of those who went to the Sierra Leone peninsula died, and the small surviving community was dispersed and the settlement destroyed as a result of a dispute between the local Temne authorities over the nature of the agreement to allow a settlement. The Temne authorities held that the settlement was on leased land, while the Sierra Leone Company insisted that it had bought the land freehold.

Vassa's observations of the scheme and the knowledge that he acquired because of his involvement undoubtedly shaped his thinking and his contributions to the group of prominent Blacks in London known as the "Sons of Africa" who wrote a number of letters to newspapers at the time that Vassa had decided to write his autobiography, and probably influenced him to do so.

Thereafter, Vassa certainly followed closely the plans for a second attempt to settle on the Sierra Leone peninsula that resulted in the founding of Freetown. His continued interest was not only propelled by his earlier involvement but also by the fact that his mentor, Granville Sharp, was the head of the Sierra Leone Company, and that John Clarkson, brother of abolitionist Thomas Clarkson, was the first governor.

Thereafter, we do not know what contact Vassa maintained with the settlers who founded Freetown, most of whom in the second wave actually came from Nova Scotia and included Blacks who had been evacuated from New York when the British accepted defeat in the American War of Independence that led to 13 colonies being established as the United States of America. But there was a clear connection. Vassa adhered to the Huntingdonian Connexion of Methodism as did a majority of the Nova Scotians. Moreover, Vassa continued his interest as recorded in his will, in which he left funds for a school in Freetown, undoubtedly associated with the Huntingdonians.