James Phillips

1745 - 1799

James Phillips was born in Cornwall, England in 1745, the son of a Quaker in the copper and iron trade. He was an international bookseller, publisher, printer, and an important member of the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade (SEAST). Phillips grew up in a Quaker family and was subsequently enrolled in a Quaker school in Rochester, Kent, and later moved to London.

His aunt, Mary Hinde (nee Phillips), owned a stationary business in George Yard, London bequeathed to her by her late husband. When she retired in 1775, she gave the business to Phillips, thus introducing him to the field of printing and bookselling. By 1783, he was mainly publishing dictionaries and bibles for fellow Quakers but also account books, stationary, French translations and educational works. As the American War of Independence came to an end, some people thought that the British economy could survive without the African slave trade, which had languished during the war. The former North American colonies had already begun discussions of outlawing the slave trade. Quakers in Philadelphia, who had long opposed the slave trade, called upon their British Friends to act against the slave trade. Many Quakers believed it to be sinful to hold a man as slave on the basis that all men were creations of God. When the London Society of Friends organized a 23-person committee in June of 1783 to discuss the issue, Phillips was one of its committee members.

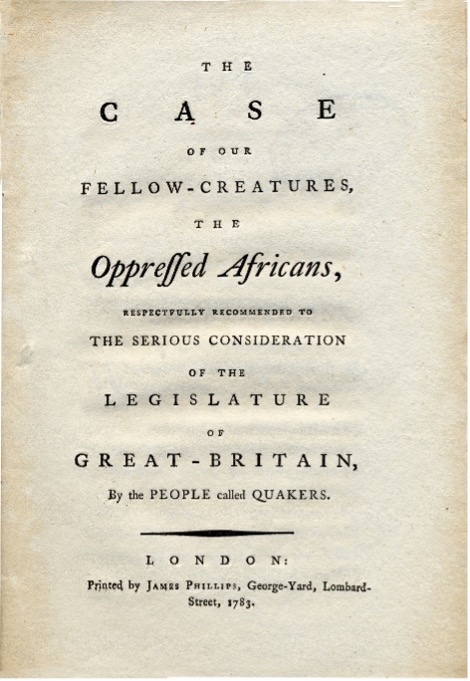

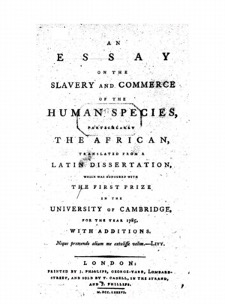

The books, papers and pamphlets that Phillips published for the Committee included the 15 page The Case of our Fellow Creatures, the Oppressed Africans, Respectfully Recommended to the Serious Consideration of the Legislature of Great Britain by the People Called Quakers, which was prepared by William Dillwyn and John Lloyd, two members of the group. After the initial printing of 2,000 copies sold out, Phillips printed an additional 10,000 copies for further distribution. In 1784, Phillips published Joseph Woods' Thoughts on the Slavery of the Negroes on behalf of the Committee with an initial print run of 2,000. Woods was a Quaker merchant whom the Committee tasked with sending abolitionist articles to newspapers around Britain. Woods argued that all Britons were complicit in the crime of slavery through consumption of slave-produced commodities and therefore were morally obligated to oppose the slave trade and pursue the issue of emancipation. Copies of the pamphlet were sent to notable individuals such as the Bishop of Chester and the Rev. James Ramsay, and various groups that showed interest in abolishing the slave trade. Phillips then publish Thomas Clarkson's Essay on the Slavery and Commerce of the Human Species, Particularly the African, Translated from a Latin Dissertation, which Was Honoured with the First Prize in the University of Cambridge, for the Year 1785, with Additions. Phillips' publishing house was located on Lombard Street in London.

In 1787, Phillips was a founding member of the abolition committee formed in London as the Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade, or SEAST. Under the leadership of Granville Sharp and Samuel Hoare, SEAST sought to inform the public on the cruelties of the slave trade.. Phillips was responsible for printing and distributing circular letters to possible supporters of the committee. The first important pamphlet was Clarkson's A Summary View of the Slave Trade.

For its official seal, SEAST asked Josiah Wedgwood, a successful businessman whose pottery industry near Birmingham revolutionized the manufacture of pottery and dishes. Phillips and Wedgewood had previously known each other through business ties. Wedgwood created a medallion that depicted the image of an enslaved man in chains with the words “Am I not a Man and Brother?” The medallion became the logo of the abolition movement and was distributed widely throughout Britain in publicizing the antislavery cause.

Phillips introduced Gustavus Vassa to Wedgwood, who corresponded with each other. In one letter, Vassa asked Wedgwood, asking him to purchase The Interesting Narrative. This solicitation is noteworthy as it is may be the first time Vassa publicly referred to his birth name Olaudah Equiano. Although the relationship between Phillips and Vassa remains unknown, it is clear they knew each other as SEAST endorsed Vassa’s autobiography, and many SEAST members subscribed to The Interesting Narrative. Furthermore, they shared mutual acquaintances such as Clarkson, Sharp and Hoare.

Phillips continued printing and publishing abolitionist literature, although none of the editions of Vassa's Interesting Narrative, such as William Cowper’s poem The Negro’s Complaint in 1788, but in the early 1790s he had a paralytic stroke, described as gout or palsy, from which he never recovered. He did rejoin the committee briefly in 1794, but the work of the committee was put on hold because of the French Revolutionary War, and thus no meetings took place for almost ten years thereafter. Nonetheless, Phillips remained an active voice in the antislavery cause until his death in 1799. His reason for his death is not documented, but his health was said to have rapidly worsened after his stroke. He was 55 years old when he died.

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Carretta, Vincent. Equiano the African, Biography of a Self-Made Man (Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 2005).

Clover, David. "The British Abolitionist Movement and Print Culture: James Phillips, Activist, Printer and Bookseller," Society for Caribbean Studies Annual Conference, Warwick University, July 2013.

The Library of the Religious Society of Friends. 1783. "The Case of our fellow-creatures, the oppressed African," The Abolition Project. http://abolition.e2bn.org/source_36.html

Vassa, Gustavus. The Interesting Narrative of The Life of Olaudah Equiano (London, 1794)

This webpage was last updated on 2021-10-07 by Kartikay Chadha