Joseph Irwin

Joseph Irwin was an associate of Granville Sharp in his efforts to protect Africans from being re-enslaved in England. He then became assistant to Henry Smeathman (1742-1786) in the generation of the first settlement project for Sierra Leone, and upon Smeathman’s death, Irwin became his successor. Vassa therefore became closely associated with Irwin when Vassa was appointed Commissioner of the Black Poor. The two men fell out over the issuance of provisions and what Vassa considered to be poor planning and leadership. In the end the Committee for the Black Poor sided with Irwin, and Vassa was relieved of his duties. He was to purchase the supplies for the black poor’s voyage of resettlement and give to Vassa the surplus provisions remaining from what was provided, to support the black poor. However when Vassa requested that of the agent, who was Irwin, he said that he did not have the necessary provisions. Vassa believed this was not the fault of the government which had provided the funds to the agent, but the fault of the oppressive and unjust Joseph Irwin, whom, in Vassa’s view, was cheating not only the government but also his countrymen. Irwin also accepted other passengers on board who were not on the Black Poor list at the expense of the government, contrary to orders.

Gustavus Vassa filed a complaint against Irwin, claiming Irwin to be a villain and Irwin made counter charges about Vassa saying that he was treating the white people with arrogance and trying to stir up anger among the blacks. Vassa accused Irwin of lying, and to prove so he brought invited Captain Thompson of the Nautilus to see how he and his people, the blacks on board, were being treated. When Captain Thompson saw, he demanded the provisions requested by the government for the black poor be supplied at once. In his complaint, Vassa reported that Irwin had only self-interest and never meant well to anyone on the voyage, leading to the death of many of the black poor.

Captain Thompson of Nautilus, after seeing the situation on board the ships destined for Sierra Leone for the resettlement of the black poor, wrote a letter to the Principal Officers and Commissioners of His Majesty’s Navy, to complain not only about Joseph Irwin but also about Vassa because of the problems their quarrelling was causing on board. He charged in his letter that Irwin did not seem to want to facilitate the sailing of the ships, and he indicated that Irwin did not have the welfare of the people at heart.

According to another source, Irwin was considered disreputable and conniving, and took on this position as agent for the resettlement for financial gain. Irwin had proven to be incompetent for this voyage and disobeyed the contract that was signed by him and the free Black people who were on the voyage.

Vassa on Joseph Irwin in The Interesting Narrative 9th ed.

By the principal Officers and Commissioners of his Majesty’s Navy.

WHEREAS you are directed, by our warrant of the 4th of last month, to receive into your charge, from Mr. Joseph Irwin, the surplus provisions remaining of what was provided for the voyage, as well as the provisions for the support of the Black Poor, after the landing at Sierra Leona, with the clothing, tools, and all other articles provided at government’s expence; and as the provisions were laid in at the rate of two months for the voyage, and for four months after the landing, but the number embarked being so much less than we expected, whereby there may be a considerable surplus of provisions, clothing, &c. these are, in addition to former orders, to direct and require you to appropriate or dispose of such surplus to the best advantage you can for the benefit of government, keeping and rendering to us a faithful account of what you do therein. And for your guidance in preventing any white persons going, who are not intended to have the indulgence of being carried thither, we send you herewith a list of those recommended by the committee for the Black Poor, as proper persons to be permitted to embark, and acquaint you that you are not to suffer any others to go who do not produce a certificate from the committee for the Black Boor, of their having their permission for it. For which this shall be your warrant. Dated at the Navy Office,

January 16, 1787.

To Mr. Gustavus Vassa, Commissary of Provisions and Stores

for the Black Poor to Sierra Leona.

GEO. MARSH.

(Pg. 227)

During my continuance in the employment of government I was struck with the flagrant abuses committed by the agent, and endeavoured to remedy them, but without effect. One instance, among many which I could produce, may serve as a specimen. Government had ordered to be provided all necessaries (slops, as they are called, included) for 750 persons; however, not being able to muster more than 426, I was ordered to send the superfluous slops, &c. to the king’s stores at Portsmouth; but, when I demanded them for that purpose from the agent, it appeared they had never been bought, though paid for by government. But that was not all, government were not the only objects of peculation; these poor people suffered infinitely more; their accommodations were most wretched; many of them wanted beds, and many more clothing and other necessaries. For the truth of this, and much more, I do not seek credit from my own assertion. I appeal to the testimony of Capt. Thompson, of the Nautilus, who convoyed us, to whom I applied in February 1787 for a remedy, when I had remonstrated to the agent in vain, and even brought him to be a witness of the injustice and oppression I had complained of. I appeal also to a letter written by these wretched people, so early as the beginning of the preceding January, and published in the Morning Herald, on the fourth of that month, signed by twenty of their chiefs. I could not silently suffer government to be thus cheated, and my countrymen plundered and oppressed, and even left destitute of the necessaries for almost their existence. I therefore informed the Commissioners of the Navy of the agent’s proceeding; but my dismission was soon after procured by the unjust means of Samuel Hoare, banker in the city; and he moreover, empowered the same agent to receive on board, at the government expence, a number of persons as passengers, contrary to the orders I received.

(Pg. 227-228)

Upon Smeathman’s sudden death on 1 July 1786, his clerk and friend, Joseph Irwin, who had never been to Africa, was the freed slaves’ own choice to succeed Smeathman as agent conductor of the resettlement project. Irwin was dead by the time The Interesting Narrative was first published.

(Pg. 299, note 639)

Thompson also complains of Irwin’s conduct (PRO T 1/643)

(Pg. 299, note 644)

Equiano may refer to the following item in the 2-5 January issue of The Morning Herald:

Irwin’s response was published in the 13 January issue of the same newspaper.

(Pg. 300, note 646)

We are sorry to find that his Majesty’s Commissary for the African Settlement has sent the following letter to Mr. John Stewart [Ottobah Cugoano], Pall Mall:

At Plymouth, March 24, 1787.

Sir,

These with my respects to you. I am sorry you and some more are not here with us. I am sure [Joseph] Irwin, and [Patrick] Fraser the Parson, are great villains, and Dr. Currie. I am exceeding much aggrieved at the conduct of those who call themselves gentlemen. They now mean to serve (or use) the blacks the same as they do in the West Indies. For the good of the settlement I have borne every affront that could be given, believe me, without giving the least occasion, or ever yet resenting any. By Sir Charles Middleton’s letter to me, I now find Irwin and Fraser have wrote to the Committee and the Treasury, that I use the white people with arrogance, and the blacks with civility, and stir them up to mutiny: which is not true, for I am the greatest peacemaker that goes out. The reason for this lie is, that in the presence of these two I acquainted Captain [Thomas Boulden] Thompson of the Nautilus sloop, our convoy, that I would go to London and tell of their roguery; and further insisted on Captain Thompson to come on board of the ships, and see the wrongs done to me and the people; so Captain Thompson came and saw it, and ordered the things to be given according to contract-which is not yet done in many things-and many of the black people have died for want of their due. I am grieved in every respect. Irwin never meant well to the people, but self-interest has ever been his end: twice this week [the Black Poor] have taken him, bodily, to the Captain, to complain of him, and I have done it four times. I do not know how this undertaking will end; I wish I had never been involved in it; but at times I think the Lord will make me very useful at last.

I am, dear Friend,

With respect, yours,

“G. VASA.”

The Commissary for the Black Poor.

(Pg. 327-328, 1 – Appendix E)

An extract of a letter from on board one of the ships with the Blacks, bound to Africa, having appeared on the 2nd and 3rd inst. in the public papers,’ wherein injurious reflexions, prejudicial to the character of Vassa, the Black Commissary, were contained, he thinks it necessary to vindicate his character from these misrepresentations, informing the public, that the principal crime which caused his dismission, was an information he laid before the Navy Board, accusing the Agent [Irwin] of unfaithfulness in his office, in not providing such necessaries as were contracted for the people, and were absolutely necessary for their existence, which necessaries could not be obtained from the Agents. The same representation was made by Mr. Vasa to Mr. Hoare, which induced the latter, who had before appeared to be Vasa’s friend, to go to the Secretary of the Treasury, and procure his dismission. The above Gentleman impowered the Agent to take many passengers in, contrary to the orders given to the Commissary.

(Mr. Vasa).

(Pg. 328, 2 – Appendix E)

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

“Black Presence.” n.d. Accessed November 19, 2021. https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/blackhistory/work_community/docs/letter_nautilus.htm.

Braidwood, Stephen J. Black Poor and White Philanthropists: London’s Blacks and the Foundation of the Sierra Leone Settlement 1786-1791 (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 1994)

Pulis, John W., ed. Moving On: Black Loyalists in the Afro-Atlantic World (New York: Routledge, 2013).

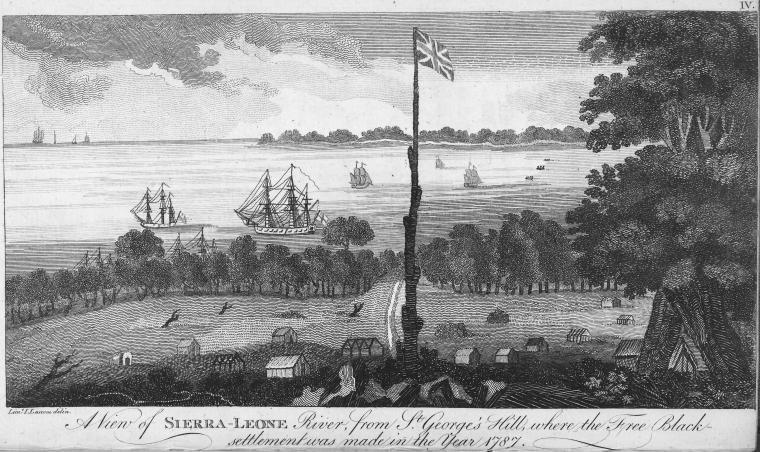

Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. "A View of Sierra-Leone River, from St. George's Hill, where the free Black settlement was made in the year 1787" New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed November 19, 2021. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47da-6fba-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Vassa, Gustavus. The Interesting Narrative and Other Writings, edited with an introduction and notes by Vincent Carretta, reprint of 9th edition (London and New York: Penguin, 2003).

This webpage was last updated on 2022-03-29 by Saloni Pande