Law Atkinson and Susannah Atkinson

(1759-1835) and (1768-1794)

Law Atkinson was born on March 13th of 1759, named after his mother, Ann Law (1738-1816). He was the first of five children born to Ann and Joseph Atkinson (1732-1807). Law was a wealthy businessman involved in the woolen industry. He and his brother, Thomas, owned Colne Bridge Mill outside of Huddersfield in West Yorkshire. The mill was targeted by the Luddites, a radical, secret organization of textile workers who opposed the mechanization of their industry in 1812. The Luddites destroyed another of the Atkinson mills, and sent letters to a local newspaper threatening to kill Thomas. In February 1818, Colne Bridge Mill burned down, killing 26, including 17 children who had been locked inside the building when their supervisor left for the night.

Susannah Atkinson was likely born in 1768 to Thomas and Susannah Atkinson, making her maiden name also Atkinson. Not much is known about her life, other than that she was extremely religious as seen through her letters to Vassa. She married Law on 29 May 1788 in Westminster, London, and was documented as a minor before the church. Law and Susannah lived first in Kirkheaton and later in Moldgreen, where Law owned several woolen and cotton mills.

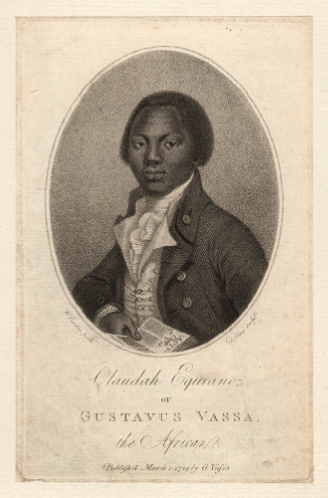

The Atkinsons were both supporters of the abolitionist movement, despite Law using cotton picked by enslaved people in his factories. They shared a friendship with Vassa, and Law subscribed to 100 copies of The Interesting Narrative. It is likely that the Atkinsons even hosted Vassa while he was on a book tour in March 1791. In the same month, Susannah wrote to Vassa, describing him as a “much valued friend” and thanking him for the portrait that he had given them. This letter alludes to forthcoming visits from Vassa, although none have been documented. Vassa mentioned the Atkinsons in a letter published on April 16 in a Leeds newspaper, thanking them for their kindness.

In February 1794, Susannah Atkinson died while travelling to Welbeck Street, where she lived before marrying Law. Her official cause of death was not publicized. At only 26 years of age, she was buried in Bunhill Fields in London. Law remarried a year later to Elizabeth Edwards, the daughter of John Edwards, a wealthy manufacturer in the cotton spinning industry who was also an abolitionist. Elizabeth gave birth to Edwards Atkinson in 1797, who would soon be joined by four other siblings, Charles (1799-1857), Elizabeth (1800-1875), Charlotte (1802-1862), and Lucy (1805-1889).

In his later life, Law was brought to court twice. He was first sued by James Carrol regarding the repossession of goods, in which Law lost in the Court of Common Please in Dublin in 1811. Law was also accused of tampering with a seal from a great coat but was acquitted in Dublin in 1813. Law declared bankruptcy in 1818 and was forced to auction off Celbridge woollen factory and its surrounding lands that he owned with two business partners, Jerimiah and Thomas Houghton. Law and his partners were able to recuperate from this blunder, and in 1833, Law was elected clerk to the Huddersfield Infirmary.

Elizabeth and Law Atkinson had a long, happy marriage until Elizabeth’s death in March of 1834. She was buried in the St John the Baptist Churchyard. Law died on March 7th of 1835, following Elizabeth exactly one year to the day, and was buried beside her. A memorial to Law, Elizabeth and their five children can be found on their family vault in the churchyard. A plaque on the wall of the church memorialized Law’s first wife, Susannah, but it was destroyed in a fire in the church in 1886. It was never replaced.

Prepared by Renée Lefebvre, 24 January 2021

RELATED FILES AND IMAGES

REFERENCES

Hern, Bill. May 2020. Olaudah Equiano and the Atkinson Family. The Equiano Society.

Orme, Daniel. March 1789. Olaudah Equiano ('Gustavus Vassa'). National Portrait Gallery, London.

Widdal, Christine. 2018. Tragic Fire at Atkinson's Mill, Colne Bridge. March 2. https://kirkleescousins.co.uk/atkinsons-mill-fire-21st-february-1818/.

This webpage was last updated on 2021-11-15 by Kartikay Chadha